Have you ever typed a website address like www.yourfavoritewebsite.com into your browser and watched it magically appear?

It feels like magic, but behind that simple action is an incredibly complex, yet perfectly organized, system that runs the entire internet. It’s a world of hidden addresses, digital phone books, and specialized messengers—and it’s all managed by three main concepts: IP Addresses, Nameservers, and the Domain Name System (DNS).

As a website owner, developer, or even just someone who wants to understand the web better, these concepts are absolutely essential. They determine who can find your site, how fast it loads, and how reliable your email is.

This guide will break down these technical subjects into simple, easy-to-digest parts. We’re going to demystify the core infrastructure of the internet and give you the knowledge you need to manage your website like a true hosting expert.

Part 1: The Foundation — IP Addresses (The Physical Address)

Before we can talk about names or systems, we have to start with the most basic truth of the internet: everything is a number.

What is an IP Address?

An Internet Protocol (IP) Address is a unique numerical label assigned to every device connected to a computer network that uses the Internet Protocol for communication.

Think of it as the exact, physical street address for your website’s home on the internet.

If you wanted to send a letter to a friend, you wouldn’t just write their name on the envelope; you’d write their street address, city, and zip code. The postal service needs those numbers to know exactly where to deliver the mail. The internet works the same way. When you want to visit a website, your computer needs the server’s IP address to know where to go.

The Two Main Types of IP Addresses

You’ll encounter two different styles of IP addresses:

1. IPv4 (Internet Protocol Version 4)

This is the original and most common format. It looks like four sets of numbers, separated by dots, where each number can range from 0 to 255.

- Example:

192.0.2.1

Since the world is running out of these addresses, a new system was created.

2. IPv6 (Internet Protocol Version 6)

This is the newer, longer format. It uses eight groups of four hexadecimal digits (numbers and letters), separated by colons. It was created to allow for a virtually limitless number of unique addresses.

- Example:

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

Why We Don’t Use IP Addresses for Everything

Imagine having to memorize the IP address for Google, Facebook, and your favorite news site every time you wanted to visit them. It would be impossible! This is why we created the system to hide the complex numbers behind simple, memorable names: Domain Names.

A Domain Name (like google.com) is the easy, human-friendly name we use. The job of connecting that friendly name to the complicated IP address falls to the next crucial component: DNS.

Part 2: The Digital Phone Book — DNS (Domain Name System)

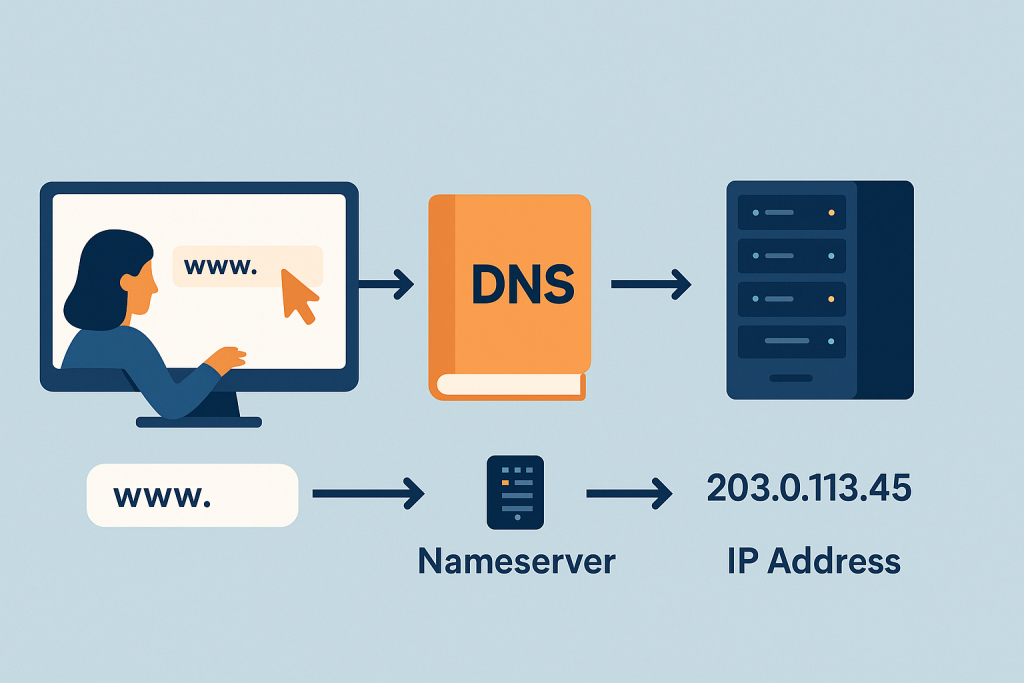

The Domain Name System (DNS) is the internet’s ultimate translator. Its entire purpose is to take the name you type (the domain name) and translate it into the IP address that the computer network actually needs.

Think of DNS as the massive, distributed phone book for the entire internet.

When you search for a name in a phone book, you get a number. When you use DNS, you type a domain name, and it gives you an IP address.

The DNS Lookup Process: A Four-Step Journey

How fast a website loads and how reliable its connection is comes down to a process called the DNS Lookup or DNS Resolution. This process involves four types of servers working together to find the correct IP address:

1. The DNS Recursor (or Resolver)

- Analogy: The Librarian at the Desk.

- What it does: This is usually a server run by your Internet Service Provider (ISP) or a public service like Google DNS (

8.8.8.8). When you type a domain into your browser, your browser hands the request to the Recursor. Its job is to go out and find the answer for your browser, no matter how many other servers it has to ask.

2. The Root Nameserver

- Analogy: The Index in the Back of the Library.

- What it does: The Recursor first asks the Root Server for help. The Root Server doesn’t know the full IP address, but it knows where to find the server in charge of the Top-Level Domain (TLD)—the last part of the address, like

.com,.org, or.net. It sends the Recursor a pointer to the correct TLD server.

3. The TLD Nameserver

- Analogy: The Section Manager for “.COM” or “.ORG”.

- What it does: The Recursor goes to the TLD Server (

.comin our example). The TLD Server doesn’t have the final IP address either, but it knows which specific Nameserver for your actual domain (yourfavoritewebsite.com) has the final answer. It hands a pointer to the Authoritative Nameserver.

4. The Authoritative Nameserver

- Analogy: The Domain Owner’s Personal Address Book.

- What it does: This is the server that holds the final, most accurate record for your domain. It is usually provided by your web host or DNS management service. It holds the actual DNS records, including the A Record that contains the precise IP address of your web server. It finally gives the IP address to the Recursor.

The Recursor then sends that IP address back to your browser, which can then connect directly to your web hosting server and load the website. This entire chain of events happens in milliseconds!

Part 3: The Direction Sign — Nameservers (The Server Manager)

Nameservers are often confused with DNS, but they are a specific, powerful part of the DNS system.

What is a Nameserver?

A Nameserver is a specialized server on the internet whose sole job is to translate domain names into IP addresses. Specifically, the Authoritative Nameserver is the one that is the ultimate source of truth for a domain’s records.

Think of Nameservers as the front-desk managers for your domain. Your domain registrar (the company you bought the domain from, like GoDaddy or Namecheap) tells the rest of the world, “If you want to know anything about mygreatwebsite.com, you need to ask its managers: ns1.myhostingcompany.com and ns2.myhostingcompany.com.”

The Key Difference: Registrar vs. Host

When you buy a domain name, you set two or more nameservers for it at the place you bought it (your Domain Registrar). These nameservers are usually given to you by your Web Host (the company that holds your website files).

- Your Domain Registrar (e.g., Namecheap, GoDaddy): The place where you pay for and register your domain name. Its job is to point the domain to your Nameservers.

- Your Nameservers (e.g.,

ns1.myhost.comandns2.myhost.com): These are the directions provided by your web host. When the whole world wants to find your website, they look at your domain registrar’s settings to see which nameservers to ask. - Your Web Host/DNS Provider: This is the server that manages the actual records (the A, MX, CNAME records, etc.). This is where the nameservers point to.

In summary: You tell the world’s registrars which Nameservers to use, and those Nameservers tell the world’s DNS Resolvers which IP address your website is on.

The Most Common DNS Records (The ‘Recipes’ in the Address Book)

Nameservers hold a file called a Zone File, which is just a list of instructions for your domain. These instructions are called DNS Records.

| DNS Record Type | Simple Name | What It Does |

| A Record (Address Record) | The Primary Pointer | This is the most important record. It points your domain name (e.g., yourdomain.com) to a specific IPv4 IP Address (e.g., 192.0.2.1). This is what tells a browser where your website lives. |

| AAAA Record | The IPv6 Pointer | The same as an A Record, but it points to an IPv6 IP Address. |

| CNAME Record (Canonical Name) | The Alias | Allows you to point one domain name to another domain name instead of an IP address. Often used to point www.yourdomain.com to yourdomain.com. |

| MX Record (Mail Exchange) | The Mailman | Tells the internet where to send your email. If you use a separate service like Google Workspace or Office 365 for your email, your MX records will point to their mail servers. |

| TXT Record (Text) | The Note/Verification | A record that holds text information. Used for things like verifying domain ownership (for Google or other services) or for email security protocols like SPF, DKIM, and DMARC. |

Part 4: The Waiting Game — Understanding DNS Propagation

You’ve just moved your website to a new host and changed your nameservers. You check your site, and it loads perfectly! You call your friend, but they say they still see the old site. What’s going on?

This is where DNS Propagation comes in, and it’s the source of most confusion for beginners.

What is DNS Propagation?

Propagation is the time it takes for your new Nameserver settings and DNS records to be updated across all the different DNS servers and ISPs worldwide.

Remember the DNS Recursor (the librarian run by your ISP)? To save time and speed up web browsing, that server doesn’t ask the Authoritative Nameserver for the IP address every single time. Instead, it caches (temporarily saves) the answer it got last time.

- When you change your nameservers, you are waiting for all the world’s ISPs to refresh their cache and get the new information.

The Critical Role of TTL (Time-To-Live)

Every DNS record has a setting called TTL (Time-To-Live). This is a number, usually measured in seconds, that tells the recursive DNS servers (your ISP’s server) how long they should hold onto the cached information before checking the Authoritative Nameserver for an update.

- A High TTL (e.g., 86400 seconds = 24 hours): Means faster lookups after the initial search, but if you make a change, it could take up to 24 hours for everyone to see it.

- A Low TTL (e.g., 300 seconds = 5 minutes): Means a change will propagate much faster, but every single lookup requires checking the Authoritative Nameserver, which can slightly slow down your site’s load time.

Propagation Timeframe: It can take anywhere from a few minutes to up to 48 hours for a full change (especially a Nameserver change) to propagate worldwide. Most of the time, it’s much faster (within a few hours), but the 48-hour window is the maximum delay you should expect.

Pro Tips for Managing Propagation

- Lower the TTL Before the Change: If you know you are moving your website, temporarily reduce your TTL (to 300 seconds, for instance) 24 hours before you make the move. This ensures that the old record will expire quickly, and when you upload the new site and change the records, the new IP address will spread much faster.

- Use an Online Checker: Tools like WhatsMyDNS.net allow you to check the propagation of your DNS records from servers around the world, giving you a real-time view of the update process.

- Clear Your Local Cache: Your computer also caches DNS information. If you’re seeing the old site, you can manually clear your local cache to force your computer to fetch the new address.

- Windows: Open Command Prompt and type

ipconfig /flushdns - Mac: Open Terminal and type

sudo dscacheutil -flushcache; sudo killall -HUP mDNSResponder(you may need to enter your password).

- Windows: Open Command Prompt and type

Part 5: Putting It All Together — A Real-World Scenario

Let’s trace the journey of you visiting www.perfectblogpost.com:

- You type:

www.perfectblogpost.cominto your browser. - Your Browser Asks: “Hey, what is the IP Address for this domain?” It checks its own small cache first.

- Your Computer Asks: It passes the request to your ISP’s DNS Recursor (e.g., the server provided by your home internet company).

- The Recursor Looks Up: If it’s not cached, the Recursor begins the four-step lookup process, eventually finding the domain’s Authoritative Nameservers (

ns1.yourhost.com). - The Nameserver Answers: The Authoritative Nameserver looks in its Zone File and finds the A Record that says

www.perfectblogpost.compoints to the IP Address203.0.113.42. - The IP is Returned: The Recursor sends the IP address back to your browser.

- Connection is Made: Your browser now knows the exact digital address (

203.0.113.42) and sends a request to that server to load the website content. - The Website Loads! The server sends the files back, and the blog post appears on your screen.

Every single time you visit a website, this chain of events happens in the blink of an eye.

Conclusion

Understanding Nameservers, DNS, and IP addresses is like getting the blueprint for the internet. These aren’t just technical details; they are the fundamental rules that make the web work.

- The IP Address is your website’s true location (the numbers).

- The Domain Name is the easy-to-remember label (the name).

- DNS is the system that translates the name into the numbers (the phone book).

- Nameservers are the managers who hold the final, authoritative records (the address book holder).

Armed with this knowledge, you are now much better equipped to launch, migrate, troubleshoot, and optimize any website. You can confidently talk to your hosting provider, manage your DNS records, and—most importantly—understand why a change might take a few hours to propagate globally. You’ve moved beyond the magic and mastered the engineering behind the web!